We parked in Chinatown and quickly made our way to the jail where Paris Hilton isn’t. Well, of course, there are thousands of jails where Paris Hilton isn’t—though if she continues the way she’s going she might see the inside of a lot more of them—but this is the one where she wasn’t most recently. That is … she was here, two days before, at the Twin Towers Correctional Facility Inmate Reception Center … sounds more like a nice hotel than a prison, doesn’t it? … the medical part of the LA County Jail, but had been moved down to Lynwood with the rest of the female population after her mysterious illness cleared up, with a little help from a court order. Interesting sidebar: At Lynwood, reporters interviewed ladies being released, and they all reported that things were fabulous inside, they’d never had it so good. Two slices of meat on the sandwiches. Extra blankets … even sheets! Unheard-of! If you reported in sick, a doctor was at your bedside in ten minutes. And cookies! They were giving out cookies! All the women had crammed their pockets with cookies. The reason? Why, the authorities were worried that in coming weeks a lot of these women would sue the County, claiming they weren’t getting the fine treatment they assumed Little Miss Hilton was getting. Will the ironies of “celebrity justice” in Los Angeles never end?

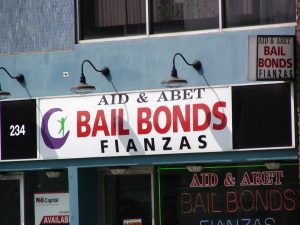

As is always the case around jails, most of the businesses around it were bail bondsmen. Some of them had a sense of humor about it. One guy would provide you a limo to drive you home from the hoosegow. Another called his business Aid and Abet.

Across Cesar E Chavez Avenue (formerly the eastern end of Sunset Boulevard) is the LA Metro headquarters, a tall building behind Union Station. There are very nice ceramic sculptures at the entrance to the Red Line terminus. Many express buses turn around here, and they were filming a Metro commercial as we passed through and entered the rear of Union Station. Thus underground, beneath all the tracks for the Red and Gold Lines, Metrolink, and Amtrak trains—we departed from here on our last trip back to Texas—and up into the simple yet grand old station itself. It’s not as big nor as ornate as some stations back east, but it’s a perfect expression of Los Angeles in the heyday of the cross-country passenger train. This is where the stars came and went in the ‘20s and ‘30s and right up into the early ‘50s. It was a more elegant way to travel, in our opinion, than the cattle cars and maximum security prisons that we call jetliners and airports these days. Sure, it took you several days, but what’s the goddam hurry?

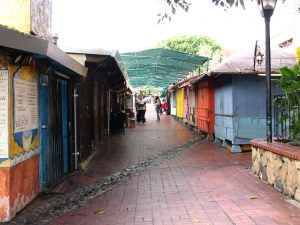

We took a short jog over to Olvera Street, the oldest part of this young city. They have finished renovations, including a nice little plaza with a little fountain and a rather violent mural that seems to be showing some sort of revolution in progress. I wasn’t able to determine what it was commemorating. Olvera was just waking up. Most of the tiny little booths crammed with cheap souvenirs were still closed, though people were raising the shutters and setting out their wares, and some were sweeping up. The little taco stands were open for breakfast, but the bigger restaurants were not. We’ve been down here many times, for one celebration or another, and we’ve never seen it so deserted. It’s all very touristy, but we like it.

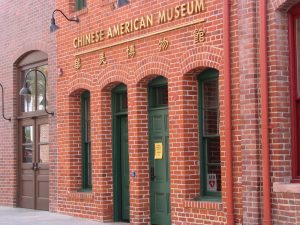

Then down through the big plaza, past the LAFD Museum and the Chinese American Museum—both closed, but we’ve seen them—to one of the major LA attractions we still hadn’t visited: City Hall.

Until 1964 it was the tallest building in Los Angeles, because earthquake considerations made that seem a wise policy. It was Los Angeles, the symbol of the city, so far as the city has a symbol, right there on Joe Friday’s badge 714. It’s held up pretty well, considering it was destroyed by Martians in 1953. Now, the towers of Bunker Hill dwarf it, due to new construction theories about how to make a tall building that can stand up to an 8-point quake … theories that have yet to be tested. But it is still the most Los Angeles building around.

We had tried to visit once before, on a Sunday, but post-9/11 paranoia kept us out. This time we got in, after the usual indignities, through the one entrance of four that is open to the public. Then, later, when we got to the third-floor grand galleries with its marble floors and columns and intricately painted ceilings, I tried one of the other doors … and it was unlocked. We were free to come and go so long as we disregarded the signs outside telling us this was not a public entrance. Yeah, yeah, if we had entered and wandered around without either a city plastic badge or the paper visitor stick-ons we were issued I suppose somebody would have stopped us and kicked our asses out sooner or later … but considering how few people we saw—and no security—it might have been long enough for us to plant our smallpox virus or dirty bomb. Now, don’t get me wrong. I think we have gone way overboard on “security” since 9/11. The terrorists just ain’t that smart, and there ain’t no such thing as security, really, just ask Lee Harvey Oswald and John Hinckley. But if we’re going to do it, couldn’t we do it well? Couldn’t we do it consistently? This goof-off, half-assed approach maximizes inconvenience to all citizens, and provides minimum protection. Worst of both worlds.

Anyway, now that I’ve vented … the building is lovely, if a bit strange. It’s quite an odyssey getting from the ground floor to the highest point where the public is allowed. First you board an elevator that doesn’t stop on floors 2-10, which delivers you quickly to the 22nd floor. Then you get on another that takes you slowly to the 26th. Then yet another that is operated by three stoned blind mice cranking on a pulley, which takes you very, very slowly up to the 27th. This is the Mayor Tom Bradley room, and it’s a cube about 5 stories high with the usual noble sentiments carved around the ceiling. Scattered around are some round plastic tables so shabby your typical inner-city junior high school would toss them away. Sort of puts the kibosh on the grandeur of the place. Two doors lead to a narrow gallery outside, where you can walk around all four sides and get fantastic views of the city. (Lots of smog, of course.) In the pictures, this gallery is at the base of the columns at the top, which I have learned is modeled on the Mausoleum of Maussollos. Funny thing to use as a model, don’t you think?

If you look at the pictures, you’ll see that there is another part sitting on top: a square, with a stepped-back taper to the very top. There are windows. What’s up there?

Well, you can’t find out on your own, because the public isn’t allowed up there anymore, because … well, just because. That’s all it takes to shut down something anymore. Because we can, and the reason is … SECURITY!!!! Never mind that, by that logic, we shouldn’t be in the Tom Bradley Room at all. I mean, really! Never mind! Forget I mentioned it, because if some bureaucrat gets the idea in his pointy little head, he’ll close that down, too. But not long ago we heard a report on NPR by a guy who had been allowed to the upper, secret chambers, and he said they were quite nice. Murals, historical stuff, all real interesting … but nothing the great unwashed “public”—who paid for it all—should be allowed to see.

From the top you get a perspective on the Disney Concert Hall that you can’t get from the ground. And looking way, way, way down by the courthouse across the street we saw the little tents of Court TV, where they were broadcasting the Phil Spector trial. Later, we went down and crossed the street and into the parking lot, where two techies, two cameras, and a single rather forlorn-looking anchorwoman were sitting around with not a damn thing to do. She had a blanket over her legs, out of camera range. Must get cold, sitting there at 6 AM for the East Coast feed. Television is such a glamorous business.

On the grounds of City Hall is a monument to Senator Frank Putnam Flint, 1862-1929, who seems to have been the political muscle behind the Grand Theft Water that enabled the Los Angeles Aqueduct to drain the Owens Valley dry and thus make possible the city of Los Angeles as it exists today. For good and ill. Appropriately, the monument is a fountain that gushes Owens Valley water all day. A toast to governmental theft!

Onward to Little Tokyo, a ghost of its former self, pre-1942, pre-Executive Order 9066, which unconstitutionally ripped just about everybody out of here, men, women, and children, and put them in concentration camps, without trial or even accusation of a crime, on some of the more unpleasant bits of American soil. Apparently it used to be about as big as Chinatown, but the residents had the great misfortune to be related to those bastards who bombed Pearl Harbor, and, even though the majority of them were citizens, born here, they were given a few days to throw away all their property and report to the bus station with one suitcase. Little Tokyo never recovered. It used to extend into large parts of what is now Skid Row, but now it huddles in about a dozen square blocks. They are not particularly nice blocks, either, though there is gentrification happening to the east, and there is the lovely Japanese American Museum, and a memorial to the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, the all-Nisei group that was the most highly decorated unit in the history of the US Army … fighting only Nazis in Europe, naturally. 21 Medal of Honor winners. Most regiments would be proud to have one Medal of Honor winner.

It’s a good place to get sushi. There are poignant quotes from internees embedded in the concrete sidewalks, lest we forget. Of course, it can’t happen again. No way. Imprisonment without trial, without charge, without a lawyer? This is America, we have habeas corpus, we have the Bill of Rights, we have the Supreme Court … what’s that? We don’t? Oh. Well, never mind. See you at Gitmo, Abdul.

By now I was into the more-dead-than-alive part of the walk, where it’s all I can do to set one foot in front of another. There wasn’t much to see, anyway, as we crossed the river on 1st Street, went north for a while on North Mission Road, and back across the river on Cesar Chavez. They’re widening the 1st Street Bridge, and Mission Road was uninteresting except for an El Pato Mexican food plant that permeated the air with the sharp but not-unpleasant smell of peppers.

July 11, 2007

© 2007 by John Varley; all rights reserved