We stayed one night at the Diamond D motel in Delta, Utah. Small as it was, it was the largest town for maybe a hundred miles. It had wide, wide streets. In most of the years since 1776, when some Spanish friars became the first white men ever to visit what the maps call the Sevier Desert, the land hadn’t been worth much, so why be stingy when surveying for streets? We had to cross the long, straight, wide main drag to get to a restaurant, and I couldn’t help wondering if I should be packing a canteen, maybe carrying a rescue beacon in case we got stranded halfway across. We were at the one traffic light in town, which had a PUSH TO CROSS STREET button that instantly changed the signal in our favor. I’ll bet that, when it was first installed, they set up bleachers so people could watch the lights change.

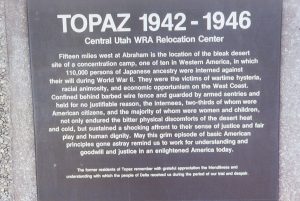

Returning after dinner, we paused in the small park in the center of town. There was a pioneer cabin, the town library, and a small stone monument. Carved into the rock were these words:

Central Utah WRA Relocation Center

Fifteen miles west at Abraham is the location of the bleak desert site of a concentration camp, one of ten in Western America, in which 110,000 persons of Japanese ancestry were interned against their will during World War II. They were the victims of wartime hysteria, racial animosity, and economic opportunism on the West Coast. Confined behind barbed wire fences and guarded by armed sentries and held for no justifiable reason, the internees, two-thirds of whom were American citizens, and the majority of whom were women and children, not only endured the bitter physical discomforts of the desert heat and cold, but sustained a shocking affront to their sense of justice and fair play and human dignity. May this grim episode of basic American principles gone astray remind us to work for understanding and goodwill and justice in an enlightened America today.

The former residents of Topaz remember with grateful appreciation the friendliness and understanding with which the people of Delta received us during the period of our trial and despair.

I hadn’t known there was a camp in Utah! I’d heard of Tule Lake and Manzanar in California, knew there were camps in Idaho and Arizona. Now I know there were camps as far east as Rohwer and Jerome, Arkansas, and Crystal City, Texas.

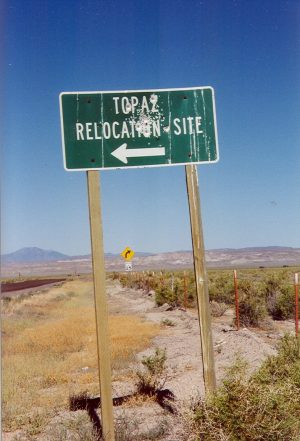

Our first order of business the next day was to drive out of Delta and find Topaz.

It wasn’t easy. Pavement gave way to gravel, then to dirt, and the only indication we were still on the right track was an occasional sign shot full of bullet holes. Finally, ten or twelve miles out of town, we saw a chain-link fence surrounding a small gravel parking lot and an historical marker. One guy had arrived ahead of us. (He was driving a Toyota, which struck me as ironic.) We read the marker, which gave just a little more information than the stone in Delta had, and had a few pictures of the camp in its heyday. We looked around. Miles and miles and miles of not very much. Not a single structure anywhere. In the distance we could see traces of green, but in the 1940s even that would not have been here. According to the Spanish explorers, what water there was in the Sevier Desert was too salty to drink. Only recently has irrigation water been brought out here, where they now claimed to grow “The best alfalfa hay in the world!” (I guess every place has to be famous for something.) You wouldn’t want to be famous for Topaz, though the town of Delta has tried to do right by the former prisoners.

You’ve probably heard of it, though it wasn’t covered in our history books when I went to school. In 1942, in the post Pearl Harbor panic, the U.S. government rounded up, without due process of law, 110,000 people of Japanese descent, living on the West Coast. We imprisoned them—we called it “interned”—in concentration camps, which we called “relocation centers.” Seventy thousand of them were American citizens, which we called “non-aliens.” And there they stayed until 1946.

Japanese-Americans have names for their generations. The immigrants, born in Japan, are Issei. Their children, born on American soil and as American as I am, are the Nisei.

The Issei were all aliens, Japanese citizens, though most had been living in America most of their lives, thirty or forty years. Technically, they were subject to round-up and internment as enemy aliens, as we did indeed do to some German and Italian nationals who had not become citizens. I say technically, because there was a simple answer to the question that always comes up concerning the Issei: “If they’d lived here so long, why didn’t the buggers become citizens?”

Because it was illegal. That’s right. Japanese could not, by law, become U.S. citizens. Their children were American citizens because they were born here, but you can bet the government would have closed that loophole if they could have figured out how to do it without endangering the rights of white folks. I don’t know if anyone ever asked the Issei how many of them would have applied if it were permitted, but my guess is most of them would have. They had put down roots here.

But nothing like the Nisei. Many of these young men and women spoke only a little Japanese, and many more spoke none at all. A feasibility study done in January of 1942 noted that the Nisei were more American than white Americans. They had bought and invested heavily in the entire American package: baseball, mom, apple pie, democracy, due process of law. The works. The study concluded it would be worse than useless to lock up this valuable resource, wasteful to assign soldiers to guard them, and, oh, by the way … it would be wrong, if anybody cared about such a concept in the anti-Jap hysteria. Nobody listened.

After a year or so men in uniforms showed up at the camps with a proposition. Enlist, they said. We’ll send you to Europe to fight Nazis and Fascists since we can’t trust you to fight the dirty Japs, being dirty Japs yourselves. And you can prove your loyalty. A lot of the young Nisei men did enlist. Then not long after came the draft notices. That’s right, somebody in the Pentagon had the unbelievable, stunning nerve to draft these boys we had put in jail, along with their entire families. Most of them entered the service. Some didn’t. I can picture it now: “What are you going to do with me if I refuse? Put me in prison?” That’s exactly what they did. And, friends and neighbors, that is where I would have spent the war years if I had been of draft age then and born with slanted eyes. I would have told the draft board to fold that draft notice enough times so it had a lot of sharp edges, and stick it up your ass.

Maybe that makes me a fair-weather American. I would have taken my imprisonment, along with my parents and family, as proof that all those highly touted freedoms promised in the Constitution and Bill of Rights were for white Americans only, and why should I fight and maybe die for you assholes? But most Nisei went to Europe, and they fought hard there. The all-Japanese 442nd Regimental Combat Unit was the most highly decorated outfit in the American military. Ever. I’ve always wondered if that was because they fought a little harder than white soldiers, having something to prove … or if it meant their white officers simply put them into more hairy situations than a regular army unit. Probably a little of both.

I didn’t learn of this episode in American history until the late ‘60s, when I was living in California and some of the Nisei were beginning to speak up about it, bring it out into the open after decades of silence. I was horrified. I immediately made a parallel to my own ancestry. My mother’s side of the family is pure German. Using the logic used against the West Coast JA’s, they should have locked her up, and her father and mother, too. After all, some German-Americans had for years been showing much more sympathy to Hitler and the Nazis than the Issei ever did for the Japanese Empire. We found plenty of German spies. We found no Japanese spies. Not even in Hawaii, where oddly enough, few citizens were interned.

Well, it was nothing like the Bataan Death March, some have said. The rape of Nanking was much worse. Concentration camps? They were nothing like Auschwitz.

Perfectly true. Not even in the same ball park. But those atrocities were done by foreign military dictatorships. The imprisonment of innocent American civilians was done by AMERICA. I hold America to a very high standard. The highest possible, in fact, else what the hell were we fighting for? Were the residents of Topaz in any way responsible for Pearl Harbor, for the Burma Road, for Okinawa? If they were, then my grandfather was responsible for Dachau.

We walked the roads of Topaz for a while. Actually, these were only wide spots among the sagebrush. We kept an eye out for rattlesnakes, which I would guess are plentiful out there. But we saw nothing. There is really nothing left to see except the endless desert landscape. Was it the most barren place I’ve ever seen? No, that would be Death Valley. But Topaz in the Sevier Desert was damn ugly. The inmates of Topaz were from the San Francisco Bay Area. I can imagine their horror at being dumped here, under guard.

There are a few concrete foundations here and there. Mess halls? Dispensaries? I don’t know. They were not the foundations for the tarpaper cabins the inmates lived in; it would take a lot of wooden huts to house the 8,000 people who were brought here. We came upon a big pile of what looked to be barrel hoops, rusting. Also some tin cans, also rusty. No way of knowing if any of those few relics dated to the ‘40s.

The town of Eureka had it wrong. This was the loneliest place in America.

July 21, 2000

Sauvie Island, Oregon