You know how you’re researching something on the Internet— say, Bassett hounds, as a random example—and you click on an interesting link, then another, and then another, and half an hour later you’re looking at a street map of Beijing and have no clue how you got there? No? Maybe it’s just me. Anyway, in the course of looking for something else I stumbled on a list of movie people who have died in 2018. These are the people we will see honored in February at the Oscars. And I saw that my friend, the director Michael Anderson, had died in April, at the age of 98.

To tell about Michael, I have to go back quite a way, to the late ‘70s.

When my short story “Air Raid” was first optioned it was going to be directed by Douglas Trumbull, famous for his special effects on 2001: A Space Odyssey. Producers were to be David Begelman (who apparently cheated most of the people he ever worked with), Freddie Fields (Judy Garland’s agent), and John Foreman (producer of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, among other fine films). I’ve told the story elsewhere of how Doug was filming Brainstorm when the star, Natalie Wood, drowned off Catalina Island. MGM discovered they could make more money by collecting the completion insurance rather than finishing the film. Doug didn’t agree, and was banned from the studio. Thus my “Air Raid” project bit the celluloid.

Maybe a year later John contacted me. The project was a “go” again. The new director: Richard Rush, whose best-known film was the excellent The Stunt Man. They went so far as to hire a screenwriter who shall remain nameless, in spite of me jumping up and down in the background shouting “I can do it! I can do it!” The Nameless One soon turned in a script which clearly showed he hadn’t a clue what the story was all about. I again waved my hand eagerly and piped up, “Can I give it a shot?” Against all expectations, I was hired.

(I didn’t tell them that I had never even read a screenplay. Why make them worry? I got some scripts, such as The Godfather, and read them while watching the finished products on videotape. They liked what I turned in.)

So Richard and I spent about three months doing re-writes, and then there was a falling out. Creative differences. Richard was fired and the film was dead again.

Now here comes Alvin Rakoff, who had done only ten films, none of which you are likely to have heard of. He had directed a lot of TV. I can barely remember him. His chief qualification for the job was that he was Canadian. By this time the potential financing involved a lot of complicated factors, chief of which was some large tax breaks if the film was made in Canada, with a mostly Canadian cast and crew. That deal fell apart for reasons I was never told.

The next Canadian to step up to the plate was Phillip Borsos, whose best film was The Grey Fox. Phil was a sweet guy, and we spent three months in Vancouver, B.C., and actually got to the point where sets were being sketched by the great Richard Macdonald, who designed Jesus Christ Superstar, Altered States, Marathon Man, and Cannery Row, among many others. Then it all fell apart again over financing. Sadly, Phil died in 1995 at the age of 42, from acute myeloblastic leukemia. He is remembered in Canada with the Borsos Awards, given out every year at the Whistler Film Festival. Tatiana Maslany, of Orphan Black fame, won it twice, in 2012 for Picture Day and in 2013 for Cas and Dylan.

I’m a little embarrassed to admit that I can’t even remember the name of Director Number Five. Five minutes is about how long he lasted.

And there you have it. Two “name” directors, one up-and-coming young man, and two what I have to say are pretty undistinguished. Almost ten years had passed by then, and we really needed someone experienced and reliable if the project was to go on. Someone solid.

Enter Michael Anderson.

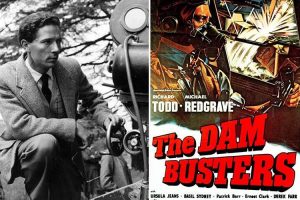

Again, he was chosen because he was Canadian, but he had one hell of a résumé. He is best remembered for The Dam Busters, the (mostly) true story of Operation Chastise, where the RAF’s 617th Bomber Squadron used a new type of “bouncing bomb” to blow up some dams in Nazi Germany, an event as legendary in England as the Doolittle Tokyo raids are in America. The scenes of the bombing runs were the inspiration for George Lucas, when he was designing the final raid on the Death Star.

Michael got his start in 1949 with Private Angelo, a comedy he co-directed with his friend Peter Ustinov. In the coming years he would direct such stars as Vanessa Redgrave, Rock Hudson, Cliff Robertson, Susannah York, Richard Attenborough, Olivia de Havilland, Anthony Quinn, Laurence Olivier, John Gielgud, Alec Guinness, Max von Sydow, Sophia Loren, Tony Curtis, Gary Cooper, Deborah Kerr, Natalie Wood, Pearl Bailey, Charlton Heston, James Cagney, Anne Baxter, Shirley MacLaine, Noël Coward, Cantinflas, and David Niven, to name a few. Phew! You want to play Six Degrees of Separation with me? By knowing Michael, I’m one degree away from all those folks. (And by knowing me, you are just two degrees away!)

He directed Around the World in Eighty Days, which won the Oscar for Best Picture of 1956. Michael was nominated for Best Director, but lost to George Stevens for Giant, a highly overrated film, in my opinion. I’m not sayin’ ATWI80D is a masterpiece of movie directing, but it’s better than Giant. Other films he is known for are Logan’s Run, 1984 and The Martian Chronicles, so he wasn’t a novice at science fiction.

We had found our solid man. No one is ever going to name Michael as an auteur, no one will say he is comparable to Kubrick or Kurosawa (but who is?). But he knew the movie business from A to … if not Z, then at least X. He knew how to get the shot, he knew how to get the money up on the screen. He was friendly with everyone, from the extras and the crew right on up to Cheryl Ladd and Kris Kristofferson, and right on down to mostly useless baggage like me. (I mean, who wants a writer on the set?)

One of the things William Goldman pointed out in Adventures in the Screen Trade (probably the best book ever written about the movie business) was that directing a film is hard work. Not only in the sense of making endless creative decisions, but like ditch-digging hard work. These folks put in sixteen- and eighteen- and twenty-hour days, for months and months, and then sweat with the editor when everyone else has gone home. Michael never showed the strain of a job that would have killed me in a week.

He was a good storyteller, and had lots of anecdotes about all those people in that list of stars up there, but I won’t repeat any of them, because most of them were not very nice stories. Plus, I’ll admit that my memory for stuff like that is spotty. I’d probably blow the punch line.

But one story I can tell concerns his shooting of one of the more ridiculous movies ever made: Orca. You may remember it; if you don’t, you’re lucky. It stars Richard Harris as Nolen, a guy who kills a pregnant orca, and then is relentlessly tracked by the father.

(An aside here: I can’t swim, and I have a phobia of sharks. Not that I can’t look at one in an aquarium, but of being in murky water when a shark is prowling about. I just about wet myself watching Jaws. But I have a rule that has served me well for over fifty years: Don’t go into the water! So Orca never impressed me much. Served the dude right. He could have moved to Iowa.)

Anyway, they were starting to shoot on Malta, where they had painted acres of rock white to simulate the polar regions, where the action was supposed to be taking place. (Because … well, what could be more logical than substituting a small island in the Mediterranean for the North Pole?) On the first day of shooting a robot whale was delivered on a flatbed truck. This was a mechanical marvel touted to be miles better than Bruce, the great white in Jaws. They lowered it into the water with the pilot on board (it was a big robot) … and it promptly caught fire and sank. The operator barely escaped with his life. So there was Michael, with a film to shoot about a whale, and no whale. “I had to fake it,” he told us. I have looked in Wiki and IMDb for this story and it’s not there, but I believe Michael.

He told me what he felt was the Number One rule of movie-making: Always have a return ticket. Once, early in his career, he contracted to shoot a film in Italy. He got there, worked for a week, and then the producers fled to parts unknown with all the money. He was stranded in Rome, flat broke. I always obeyed that rule.

I don’t blame Michael for Millennium. As I have stated elsewhere, after ten years of development hell, six directors, nine producers, eight re-writes and countless “polishes,” the life had been squeezed out of the script. Michael did what he had been hired to do, which was do the best he could do with the material. To quote Goldman again: “Nobody sets out to make a turd.” You can gold plate it, but it’s still a turd.

Michael had not worked for almost twenty years. I have no idea if it was his choice, or if it was a matter of being unable to find work. I’m going to believe that it was a happy and planned retirement. I will imagine him spending cozy winters in the little brick house in Toronto where I went with the producers and stars for dinner one cold evening.

Interesting facts gleaned from Wiki: He won a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Directors Guild of Canada in 2012. And at the time of his death he was the oldest living nominee for the Academy Award for Best Director. He was truly a link to another era, and I’m sorry that he’s gone.

John

December 31, 2018

Vancouver, WA