Right after Christmas last year we drove home from Las Vegas and detoured north to Death Valley. We went to Scotty’s Castle, and on the way there a coyote flagged us down and tried to hit us up for scraps. We explained to him that the road signs clearly stated that we were not to feed the wildlife. He didn’t take this happily. Coyotes, eh? What can you do?

We like deserts, to drive through, and as long as it isn’t the hot season. I don’t know how people can live there, but it takes all kinds, right? We were impressed by the sheer desolation, the huge salt flats, the tortured rock, the eroded landscape. We learned that, in the summer, the ground temperature could reach 180, 190 degrees, literally too hot to walk on, even with boots.

At the castle (which is a mansion that looks like a castle, and which never really belonged to Scotty, who was a prospector, performer with Buffalo Bill, charlatan, charmer, and big liar) they told us the best season to see the valley was March, when the wildflowers bloomed. We decided to go back, some day.

Even in December the rains had been so heavy for the area that several roads were washed out. More rain followed, a record season for the whole Southwest. We began hearing stories about the flowers in the valley, which were said to be more bountiful than they’d been in 100 years. So we set out early one morning in March to see this centennial wonder.

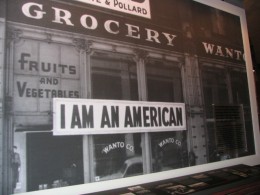

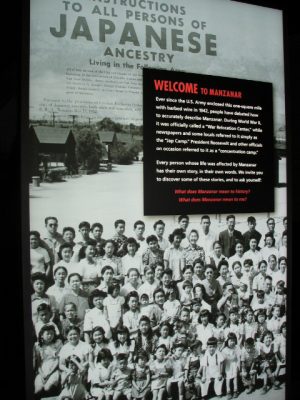

On the way there we remembered that, last time through, we had come very close to Manzanar, and vowed to return for a visit. Who knows how long it will be before we return, so at the pretty little tourist town of Lone Pine we continued about five miles until we reached what used to be the Manzanar War Relocation Center, now a National Historic Site.

We had been to one WRC … oh, the hell with that government bullshit, it was a concentration camp, okay? It was one of ten the United States of America, the greatest democracy in the world, operated between 1942 and 1946. You say you don’t like those words, “concentration camp”?

Definition: A place where they send you without your consent, not for anything you did, but because of what you are. You stay there, without any sort of sentence, until they decide to let you out or kill you. QED.

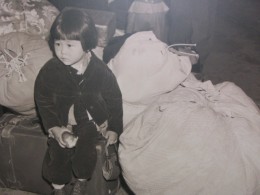

Franklin D. Roosevelt sent 110,000 people of Japanese descent to these camps during the war. The majority of them were American citizens, born right here. The others were not citizens for a simple reason: it was illegal for Japanese-born persons to receive citizenship in the great melting pot of white Americans.

We didn’t know what to expect at Manzanar. The one we had previously visited, Topaz, just outside of Delta, Utah, was hardly there at all. Nothing but a small gravel parking lot, a cyclone fence around a plywood sign with pictures and some text on it. That was it. We drove around a little and found a few concrete foundations, but the place had been scraped right down to the desert, as though somebody in government might have been shamed of it. I wonder why? The setting is bleak.

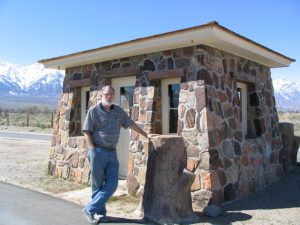

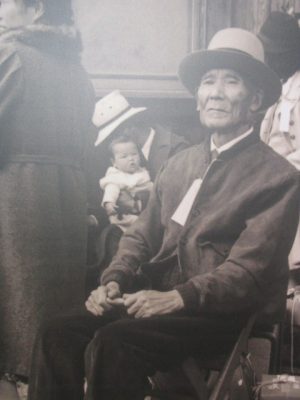

Manzanar is in a beautiful location, set against the snow-covered peaks of the Eastern Sierras. It’s a place you might like to go, if you had a choice, though it is bitterly cold in winter and hot and dusty in summer. Three of the original camp buildings still survive. There are two tiny ones, made of stone by the inmates themselves: guardhouses, one for the military, and another one just past where the barbed wire would have been, for the internal police, who were Japanese. The National Park Service has done some nice work. There is a large, ugly (on the outside) “interpretive center,” which is what they’re calling museums these days, made from the old camp auditorium. There is a big paved parking lot. Admission is free. Inside are many great exhibits, including a huge canvas hanging with the names of all 10,000 of the former inmates.

There was far too much to see in the museum for such a brief visit, but two highlights I read were worth remembering. The original director of the place resigned in, I believe, June of 1942. He told his successor that he shouldn’t take the job unless he thought he could do it and still sleep at night. The new guy apparently didn’t have much of a heart or didn’t need much sleep. He lasted the whole time. And the story was told of a veteran of the 442nd Division, all Japanese-Americans fighting in Europe, the most decorated outfit of WWII. He boarded a bus in full uniform with all his medals, and some bitch started ranting at the bus driver to get that dirty Jap off the bus. The driver, a veteran himself, stopped and told the woman, “Apologize to this American soldier, or get off my bus.”

On the way out we heard the park ranger talking to a white guy, asking him if he’d been to Manzanar before. The guy wasn’t sure. He had been to one of the camps with his family to visit the Japanese family that had worked for them as tenant farmers. He was too young to remember which camp it was. He couldn’t recall their names, either, in which case the ranger could have helped him, as there was voluminous data on each inmate. All the guy remembered, he said, was that when the Japanese family was released after the war and came back to the farm, they were very bitter. Gee, I wonder why?

The rest of the grounds is mostly a series of signs showing where things used to be: Victory Gardens, Block 14, Block 15, etc., Hospital, Children’s Village (for orphans), Ornamental Gardens. There is a monument in the graveyard—which had few actual graves in it; most of the people who died there were shipped elsewhere for burial. People have festooned the area with bright origami papers, now faded in the sun. There is a pet cemetery nearby.

I felt good to have gone there to pay my respects, and to offer my silent apologies to those we treated so badly. I hope to one day visit them all: Tule Lake, Minidoka, Heart Mountain, Manzanar, Topaz, Poston, Gila River, Rohwer, Jerome, Granada.

Two down, eight to go.

* * *

We descended into Death Valley from the west, and immediately could see the change. It was pretty spectacular.

I have to qualify that, however. If you’d never been to Death Valley, if you’d never seen just how much “Death,” or at least “lack of life,” is the theme around there, you might not even know you’re seeing something extraordinary. You can drive 10 miles in any direction from where I’m writing this (Oceano, Cahleefornia), except west, and see far more impressive displays of wild flowers than you will see in Death Valley today. Part of the charm is realizing how miraculous it is that plants can flourish and bloom in this place at all. Many of the flowers are extremely tiny; you have to get out and get close to see them. Some are rare, and only to be found by the determined hiker, which I am not.

But having said that … it is gorgeous! There are miles and miles and miles of the most prominent flower: the Desert Gold, Gerea canescens, a sort of yellow daisy. There are also banks and clumps of a small purple flower whose name I don’t know. We got out and Lee snapped away with her new digital camera, both panoramas and close-ups.

We visited the ruins of the old borax mill that was about the only excuse for humans to go there for a long, long time. I don’t think even the Indians went there often, or tarried long. There is one species of big game, the bighorn sheep, one big predator, the coyote, that live in the harshest parts of the valley; everything else is a rodent, a bat, or a reptile. Nothing to eat, and only 5 inches of rain in a good year.

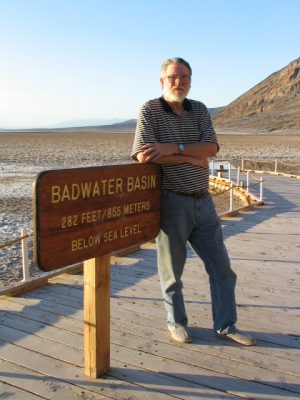

Then on to Badwater, the lowest point in the Americas. They have an excellent illustration of that. About halfway up the mountain that borders the viewing area is a sign: SEA LEVEL. You have to crane your neck to see it. The “lake” is full of water, all the way across the valley. There are canoeists and kayakers out there, and even if you paddle out to the middle you can step out of your boat and seldom be in over your waist. Flat! Also, very beautiful, mirroring the mountains behind it. Some very rare fish live in the pools that last any time into the summer, but we didn’t see any of them.

A trip well worth taking, if you’re within driving distance for the next month or so.

One more thing: bring some Windex and paper towels. When flowers bloom in Death Valley, the bugs do, too. We had to wipe them off the windshield twice if I was to see out at all. I haven’t even tackled the front bumper yet.

* * *

I have to return to Manzanar here at the end. Driving back that night, I had plenty of time to think about why the camps affect me so much.

On the scale of historical atrocities, Manzanar is small potatoes. It can’t compare to the Nazi death camps, or to any number of camps operated by the Empire of Japan for both POWs and civilians. It wasn’t The Bridge On the River Kwai, it wasn’t Schindler’s List. Even on the scale of atrocities committed by the United States of America, my beloved country, it doesn’t measure up. It was nothing like the genocide of the Indians, and nothing like slavery.

The thing is, it was the worst example of fascism in my country in the twentieth century. Fascism is not a term I throw around lightly, but if the jackboot fits …

I’ve never called the American police or the military fascist institutions, though individuals with guns in positions of authority are sometimes tempted to behave that way, and sometimes do. When they are caught at it, they are tried and punished, which is as it should be. That’s what democracy and the rule of law are all about.

And that’s the key: the rule of law, under a constitution. Executive Order 9066, the one used to round up all Japanese on the west coast regardless of age, sex, or citizenship, without charges of any sort being filed, and their internment with no sentence ever having been pronounced, was fascism of the purest kind. It was eventually found to have been unconstitutional, and after a very long time reparations (entirely symbolic and having no relation to the amount of financial loss incurred by the illegal seizures of property) were paid, and that is good. The Reagan Administration even apologized for the flouting of the law by the Roosevelt Administration, and that was important, too.

The thing about fascism is, most if not all of us have the capacity for it in us. That impulse to trade civil liberties for a sense of security is strongest of all during wartime. The “Day of infamy,” December 7, 1941, was followed within months by the establishment of places whose names will live in infamy, such as Manzanar.

Now we’ve had another day of infamy, September 11, 2001, and many of us have begun to get the whiff of fascism at work again. Just a little stink at first, but it’s hanging on, and it’s growing. I believe that, if the United States of America survives more or less as it has been for the last century, the name Guantanamo Bay will live in infamy, too.

Frankly, I don’t really much care about most of the individuals currently being held there without charges, or access to lawyers or the outside world, (see, I have fascist tendencies myself), any more than I care if some scumbag rapist/murderer gets killed in a shootout with police. Most of these people were captured in Afghanistan, after all, plotting atrocities against Americans and others. They need to be locked up. You could even say they are prisoners of war … if we had bothered to declare war, which we haven’t since 1941. So what’s the big deal?

Well, aside from the aforementioned lack of due process, to which everyone is entitled, even the worst of us … I said most of them were probably members of Al-Qaeda, picked up in Afghanistan. There are others, at Guantanamo and in other places, that were picked up in Iraq, in Yemen, and even in the good old US of A. What are they there for?

That’s the point. I don’t know! I don’t know their names or their alleged crimes. If that isn’t a hallmark of fascism, I don’t know what is. I don’t want them let go. I want them named, and I want them charged with something, and then I want them tried!

Our legal system is currently tackling this situation, and that’s good, but it moves ponderously. It could easily be ten years before a final determination is reached. In the meantime, it goes on and on and on.

The Bush Administration has even introduced a new twist: fascism-by-proxy called “extraordinary rendition.” Surprised by the uproar about Abu Ghraib (nothing but a boisterous frat hazing, according to Rush Limbaugh), they have farmed out things that are deemed too raw to dirty American hands with, i.e., torture. As I write this the CIA is moving prisoners on private jets to places like Syria and Egypt and Yemen, all places eager to suck at the American tit, none of them as queasy about “vigorous” methods as we are. Again: no charges, no names, no trials. If you have an Arabic name you can be plucked up at any moment and flown to one of these places, and quite possibly never be heard from again.

So those were my thoughts, driving home from Manzanar. In fifty years, will people be standing at the site of old Guantanamo Bay Military Concentration Camp, reading the signs explaining what went down here? Will they visit the Interpretive Center and see the exhibits of … what? We don’t know what’s going on down there. No one can visit. But you can be sure records are being kept. Fascists are renowned for that. It will all come out, and some future administration will tut-tut, apologize, and assure us that “It can’t happen again.”

But it can.

March 23, 2005

Oceano, California