“Oh, bother,” said Pooh …

… as he stripped off his little red T-shirt.

When I was very young one of my favorite books had a map on the inside cover. It was probably the first map I ever looked at. It was of the Hundred Aker Wood, and it had place names like Owl’s House, Pooh’s Hunny Tree, Where the Woozle Wasn’t, and Trespassers W, where Piglet lived.

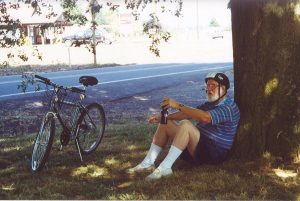

We’re making our own map of Sauvie Island, adding a place or two every day as we take our daily walks. Sauvie is considerably larger than 100 akers, so we’re not likely to run out of places soon.

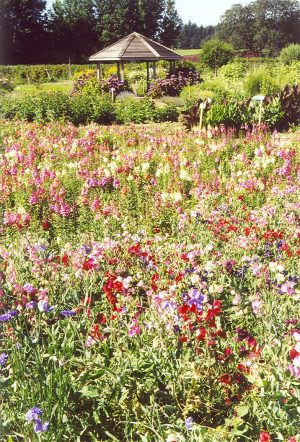

There are the places that everybody knows about. Sam’s Cracker Barrel Grocery. Reeder Beach, where we live. The Blue Heron Herbary and the Exuberant Gardens. Houseboat Village. The U-Pick flower field, faithfully guarded by Sally, an old, fat, one-eyed Black Labrador, whose idea of guarding is to approach visitors with a big clod of dirt in her mouth and lay it at your feet. I pick it up (eventually; she is deeply conflicted about letting me have it, though she is all aquiver in anticipation of chasing it), and I throw it for her. Naturally, the clod shatters into a million pieces and she casts about in frustration, wondering where in hell it went, and where in hell she’s going to get another dirt clod as fine as that one was. What a life.

What she’s guarding is a bucket of money. This is something you don’t see every day in the city. It’s just an empty paint can, and inside is the money people pay after they’ve picked their 3-for-a-dollar tulips and wrapped them in the newspaper the U-Pick people provide. Okay, there’s never a LOT of money in it. But they are also selling hanging fuchsia baskets which they’re asking $19 for, and they’re just hanging there. There’s a bucket full of plant shears, too, free to any thief willing to endure the bad karma one would incur by such a rotten theft. We’ve seen this arrangement before in the country, at dahlia patches. Makes you wonder a bit. Maybe this business of everybody moving to the city is a big mistake.

There’s other geographical features on the map, like Sturgeon Lake, a pretty large body of water entirely enclosed by the island. There are even islands in it, and maybe little lakes in THOSE islands. There’s the Collins Clothing Optional Beach (where Christopher Robin is spending more and more of his time now that he’s no longer Very Young, and if Pooh is too modest to go along he can just get stuffed, silly old bear).

Then there are the places we’ve named ourselves because they tickled our fancy or because we saw or heard something unusual and worthy of note. Well, noteworthy in our present under-stimulated state, anyway. Places like the Six Duck Blinds Marsh, Eagles Roost, the Other Eagles Roost, Carp Flop Lake, Where Something Big Jumped in the Water and Scared Lee, and Nutria Pond.

(Completely off-the-wall rumination: When my mother first read the Pooh books to me, I thought Christopher Robin might be a girl with a strange name, because in most of the pictures he was wearing a dress. Only later did I learn this was just the way upper class Brits often did things in that era. I’ve seen pictures of Winston Churchill, age 4 or 5, in a dress. Do you suppose Sir Winnie might have developed a fetish about that? I’m picturing him in a suitably frumpy frock, stumbling around 10 Downing St. in high heels. And if you think that image is ghastly, how about Churchill going on a double date with J. Edgar Hoover? Maybe with Maggie Thatcher and Janet Reno? The mind reels.)

Anyway, we’ve gone loopy enough out here in the sticks that I’ve taken to naming our favorite fine feathered, furry, and even slimy animal friends.

* * *

Alfalfa the Frog

I keep thinking of the little tree frog I found in the shower a few weeks ago. Worried that the hot water would kill the critter, I caught him in the soap dish and put the top on it. Then I carried him outside and let him go. I noticed he was even slipperier than a frog usually is. Soap, from inside the dish.

So I see him finding his home pond, hopping up onto a log with his buddies to tell them about his weird adventure. He opens his mouth to croak … and a stream of bubbles comes out, like when Alfalfa swallowed a bar of soap and tried to sing.

* * *

Eddie the Eagle

When we first started living out here we were getting up and out early in the morning, when the sun was just rising. For several days in a row we saw a bald eagle perched in the same place every morning. Then we didn’t see him for a while, maybe because we weren’t getting out so early. A few days ago we saw him again—or possibly another—at the same perch.

Coming back in the evening he was there again … and so was somebody else. What may have been a red-tailed hawk (it’s hard to tell even with binoculars when they’re silhouetted against a bright gray sky) was trying to pick a fight with the eagle. No kidding. He came swooping toward the eagle, and in the last ten feet or so he held his talons out in front of him, ready to claw the eagle to shreds. But the eagle wasn’t about to give ground. He spread his wings out and opened his mouth and just stayed there, giving a pretty good imitation of the “tails” side of a quarter.

The hawk was impressed, too. He was almost as big as the eagle, but not quite. And when those wings went out he broke off his attack and swooped away … then gained altitude and came back for another try! Same result. The hawk decided that was enough for today and flew off over the horizon. I think he was lucky to escape with his life.

Speaking of quarters … I got one out and looked at it. That’s exactly how he looked. And right over his head was his name: E. Pluribus Unum. Now I figure nobody really wants to be called Pluribus or Mr. Unum. Guessing the E. stands for Edward, I’m calling him Eddie the Eagle, like that Brit ski jumper who always landed about half the distance the Finns and Swedes were getting.

* * *

Dagwood and Blondie

We have two ospreys nesting on the channel marker no more than 150 yards from our trailer. (2002: They have nested there for three years now. Every winter whoever handles such things as navigation lights for the state comes around and clears the big nest of branches, tossing it all in the Columbia. And every spring, Dagwood and Blondie are back at their domestic chores, rebuilding the nest. They make quite a big one. About 40 or 50 yards from the channel marker pylons is a single, tall one. When Blondie is sitting the nest, Dagwood perches out there and looks for fish to kill. When he gets one, he takes it to the nest and holds it down with one claw and rips off bleeding hunks of flesh and offers it to the one or two chicks (this year, apparently only one). They open mouths that, I swear, are wider than their heads, and gobble it all up.

* * *

Rockin’ Robin

Today marks the 14th day the robin has been attacking our car. I say attacking, because the majority of you told me that’s what this behavior was all about. But after yesterday we’re not so sure. Lee observed him leaping with a twig in his mouth. Do you figure this was a rare example of tool use by an animal? Did he figure to whack the crap out of that other robin with the stick? Or could he be trying to convince his lady love that it was time to get serious and start building a nest?

He’s looking a bit thin these days. I haven’t tried any of the remedies several of you suggested. Can’t afford a custom car cover, and a sheet would look tacky. Can’t afford to look too tacky in a trailer park. As for taping over the chrome … this adds up to almost 40 feet! A Buick Park Avenue doesn’t stint on the chrome, like the new cars you see these days. I think I may try silver Mylar strips, if I can find some.

Tired of referring to him as “the robin,” we’ve decided to name him Rocky. You gotta admit, he’s a hell of a fighter.

DAY 17: He’s taken to gathering a beakful of grass clippings before he once more assaults the robin in the Buick. Does this sound like fighting behavior?

DAY 21: I studied the chrome on the Buick a little more closely today, and found a detail that may be important. As I said, the strip is 3 inches wide, and runs completely around the car except the wheel wells, about 18 inches above the ground. Angled slightly toward the ground, so standing a few feet from the car the robin can definitely see himself. But now I see the chrome is just slightly convex. This would mean the robin’s reflection is just a bit smaller than the robin himself. I’ve read that when elk, elephants, lions, walrus, or other large beasts tangle, it is invariably the larger one that wins. Could Rocky know that? Could it be that he simply KNOWS he is destined to win out over this incredibly spunky pipsqueak that lives in the Buick?

DAY 23: He’s gone. At least, it’s 10AM and I haven’t seen him yet. Could he be dead of starvation, or injuries? I hope not. Possibly he finally gave up, or maybe he finally found a female so gorgeous he could forget about his implacable opponent. I did find a tiny towel on the ground near the car. Do you suppose Rocky threw it in? You know, he could have been a contender. And what happened? A one way ticket to palookaville. I see him standing in a clearing. He carries a reminder of every glove that laid him down or cut him till he cried out, in his anger and his pain, “I am leaving! I am leaving!” But the robin still remains.

DAY 26: He’s back.

* * *

Saw a blue heron flying over the trailer today. It had a stick in its mouth, obviously on the way to a spring building site. The funny thing was, I watched him out of sight, and he was headed straight over the Columbia, toward Washington. I told Lee about it and, true born-here Oregonian that she is, she figured it out immediately. Why would a heron get sticks in Oregon and build a nest in Washington? Simple. He lives in Washington because there is no income tax up there. He shops in Oregon because there’s no sales tax down here. Probably got a heck of a deal on that stick at the Heron-Mart.

* * *

I must have seen a thousand nutria when we were living on the Texas Gulf Coast. Every one of them was road kill, smeared all over the highway. Some of them were almost as big as a beaver.

The story on nutria was that they were brought over to the U.S. from South America to eat the water plants that grew so quickly in the Intercoastal Canal, a man-made waterway that stretches from the Florida Keys to Brownsville. Trouble was—and this should have been obvious, it seems to me, given the breeding habits of rodents—very soon there were WAY too many nutria. They burrowed into the sides of the canals, which caused them to collapse and ended up making even more work for the dredges. Pretty soon there was a bounty on them. Not that it did any good. Like kudzu with hair.

But the wildlife book I have says they were brought over for fur-ranching. Places in Louisiana bred them in cages, like minks. Then there was a big hurricane in 1940 and many of the fur farms were destroyed … but not the nutria. They vanished into the swamp and began doing their little rodent thing. Soon they were crowding out native species. Same old story. Why, oh why, do people keep trying to bring in alien critters to solve some problem? Seems to me that, 99% of the time, they end up wishing they had the old problem back instead of the new problem the “solution” caused.

Oregon was the last place I expected to see nutria. But not long ago we were looking into the stagnant canal that runs about 50 feet behind our trailer and Lee said “That floating stick just moved!” I thought it was just a stick, but pretty soon it swam to the side of the canal and climbed out, pretty much ruining the stick theory. My guess was muskrat. The book, and a neighbor two trailers down, said no, it was a nutria. We saw well over a dozen of them without looking too hard. They swim with their tails, with just their noses out of water.

There was a map in the book and sure enough, nutria habitat was all of the Gulf coast, more than half of Texas … and the Pacific Northwest coast. They live in Chesapeake Bay, and there are even pockets in Montana, Nevada, and Wyoming. Those must have been epic journeys for a bunch of water rats.

* * *

Carp Flop Lake

At the very far end of Reeder Road, getting close to the northern tip of the island, the road turns to gravel for a few miles then stops at a gate beside a cow pasture. Now that April 15 has come and gone we are able, legally, to go beyond these gates without a hunting permit. We did, sometimes walking on a forest path, sometimes on the beach. After a mile or so the path curved deeper into the woods and we soon came to another of the shallow lakes that dot Sauvie Island. (Possibly a bay; we couldn’t see what was at the far end, whether it connected with the river.) This is the kind of lake that begins with a fifty-foot stretch of mud before you get any real water. Another fifty feet and the water is two or three inches deep, and grass is still growing in it. I wouldn’t be surprised if one could wade all the way across it, though it is quite wide.

The water in the grass at the edge of the lake seemed to be boiling. Some large fish were thrashing around in it, as far as I could see. Neither of us was willing to get in really close since we were wearing walking shoes, not boots or waders. But we could see the dorsal fins even as far away as we were. Seemed sort of silvery. We thought, but couldn’t be sure, that these were pairs of fish. Mating? Spawning? Probably. But what were they? All I could think of was salmon, but I thought they all went a lot farther upriver than that.

Back at Reeder Beach our neighbor, Dan, a fisherman with two boats parked behind his trailer, said it was probably carp. Too bad. With boots, you could have splashed up to them and picked them up with your hands, or a net. But I’ve never seen carp on a menu, and I seem to recall hearing they are mighty poor eating.

* * *

The next day we took another trail that went up over the levee and gave us a view of a very wide meadow. There were cattle grazing on the areas of open grass, substantial patches of woods, and half a dozen little ponds. We had spotted several bald eagles there on a previous walk.

All the ponds had carp flopping around in them. Not nearly as dense as Carp Flop Lake, but the sides of some of these ponds were a lot steeper, and we were able to get a lot closer before the fish spooked and headed for deeper water. The thrashing about was definitely being done in pairs, and what I could see did look a lot like carp.

It occurred to us that getting into water that shallow was a bit dangerous with all those eagles around. The carp probably wouldn’t be doing anything that foolish if it didn’t have to do with sex, which, as we all know, can make the most rational animal do things of monumental stupidity. (In fact, most of us can speak from personal experience, though I’ve never flopped around in shallow water, making myself eagle bait.)

Sure enough, a few minutes later Lee spotted a dead fish. Well, 2/3 of one. There was the head with a few bones attached, and the tail. The middle part was gone. It was definitely a carp, with the little growths called barbels around the mouth.

We went on, had a little confrontation with a killdeer (more about that later), and then saw a bald eagle swoop down and disappear behind a low rise, at what I thought was the exact spot where we’d seen the dead fish. We hurried toward it, but before we got there another bird, at least as big as the eagle but all brown, no white head and tail, headed for the pond. The bald eagle took off and started to gain altitude. The other bird followed, eventually overtook the first bird and began attacking him. It was a regular dogfight, all it needed was the sound of howling engines and trails of black smoke. At one point both of them were falling through the air, raking at each other with their talons. It was exciting! It took our breaths away, I promise you.

Finally one or the other gave up—it was all too distant for us to be sure even of the breed of the other bird—and the bald eagle flapped away into the distance.

When we got to the spot where the fish had been, the tail was gone. We’ll never know which bird got it.

* * *

Olivier, the Killdeer

A killdeer is a smallish bird that I used to see by the thousands on the Texas Gulf Coast. If you walk toward them they’ll run a long ways on their skinny legs before finally taking wing. We had seen and heard one at Reeder Beach about a week earlier. Seems they like river environments, too.

Just before Lee found the dead carp we were vastly entertained by a killdeer that really ought to have an Oscar. We were skirting one of the shallow lakes and he seemed real interested in us. He would run along the water a ways, then crouch down sideways, angling the top of his body toward us. He’d spread his wings slightly, and fan out his tail a LOT, revealing a lovely brown and black and orange and white pattern. He’d hobble and shake in that posture for a while, then walk some more.

I wasn’t fooled. I’d heard that some birds that nest on the ground will fake a broken wing, flap and flutter all over the place to lure foxes and weasels, etc., away from the nest. So we looked for the nest but couldn’t find it. When we were a safe distance from where the nest must have been, the killdeer flew off.

We got back to the trailer and got out the Audubon book, looked him up … and the book described EXACTLY the behavior we observed.

I can’t tell you how gratifying that is. So much of what I know about nature is the result of some very clever and determined people slogging up mountains and through swamps and climbing trees in the rain forest, freezing or sweltering, living in clouds of bloodsucking insects … all to get a snapshot or a bit of film that I can watch on the Discovery Channel.

I never expect to actually SEE these things with my own eyes. And, sure, Sauvie Island ain’t exactly the depths of the Amazon. But every once in a while you CAN see amazing things, if you keep your eyes open.

* * *

A FEW DAYS LATER

We went back to the same place, hoping to take another shot at finding Olivier’s nest. But it had rained hard the day before. All the little lakes were a lot larger; some had joined together. It was all draining, but slowly. We wondered if Olivier’s nest had been built far enough from these new lakes. Seemed unlikely we’d ever find out. We didn’t even see any killdeer, though there was a covey of common snipe. Believe me when I tell you that, until I found them in the Audubon book, I thought the whole race of snipe was an invention of boy scouts and other summer camp sadists who took gullible tenderfoots out into the woods at night and left them there until morning, holding a gunny sack open for all the snipe the others would soon be herding their way.

The new residents of the big meadow were swallows, darting all over the place. These had the same paint job as a World War Two Navy Corsair fighter plane: dark blue on top, pure white on the underside.

* * *

We don’t spend ALL our time hanging around the trailer or romping through the swamp in search of birds. On Bad Saturday (the one between Good Friday and Easter Sunday) we made an excursion in the car. Out to the coast, south for a while, then looping back on some of the very few roads in this part of the state that we hadn’t yet traveled. A good part of that trip was in the deep forests and along the Pacific beaches of Clatsop County. Like so many place names here in the PNW, Clatsop was named for a tribe of Indians that ran things around here until the arrival of the paleface.

Much lesser known was a group related to the Clatsops: the Catsup tribe. These people inhabited the malarial marshes and bogs and any other land of questionable value in the deep woods. Though it meant they were a very poor tribe, at least no one ever tried to take their land from them. Nobody wanted it.

The Catsups were best known for a dark red condiment they made, a concoction they called “red mash,” and the neighboring Clatsops called “bug killer,” or “Catsup’s revenge,” or “Turns-your-piss-red.” For some reason the Catsups stored the stuff in tall, narrow-necked pottery made especially for this purpose.

Depending on the season, red mash was made from cranberries or beets, both of which grew wild on Catsup land. The tribe traveled as far as Sauvie Island on the Columbia in search of the wild wapato root, which they sliced in narrow strips, deep-fried in skunk fat, and dipped in the Red Mash. It was the staple of their diet. None of the other tribes in the area could stand the stuff. (Unknown to the Catsups, their red mash would have gone quite well with roasted turkey. They didn’t know this because there were, and still are, no wild turkeys in Oregon. Until the opening of the Oregon Trail Indian and settler alike had to eat scrawny old roast eagle and all the trimmings on Thanksgiving Day. They stuffed some old bread in it to make it look a little fatter.)

In 1885 the Federal Government sent an expedition into the bog to make peace with the Catsup Tribe. It’s not that the Catsups had ever actually been at war with anybody, but no one could find a signed peace treaty no matter how they searched. Without a peace treaty it was deemed well nigh impossible to give them the official screwing all the other tribes in Oregon were getting, so there was some urgency to the mission.

In charge of the expedition was one Colonel Mustard—Colonel Heinz Mustard, to be precise—a man born in Hamburg, Germany, who immigrated to America in his early twenties. Second in command was Captain Huntz Pickles, a man with a similar history but hailing from Frankfurt. Inevitably, their men called them the Two Krauts.

The two together, Hamburger and Frankfurter, made a highly motivated team and they went about their assignment with relish. This happened to be the year of the Great Cranberry Famine, when all the bogs dried up and there was nothing for the Catsups to eat except boiled skunk, lettuce, and tree bark. They quickly surrendered to the Krauts and pleaded to be fed. As fate would have it, most of the expedition’s provisions consisted of bacon, buns, beef, and tinned tomatoes. The Catsups eagerly wolfed down the food given them by the cook, wrapping it all in the bread and adding a few chips of tree bark, just narrowly missing inventing the BLT.

But the Catsups planted the seeds of this strange new plant the white man brought. When the vines bore fruit they prepared them as if they were very large cranberries and poured the result into their narrow-necked pottery containers. Colonel Mustard loved the stuff! He took the recipe with him when he left after signing the peace treaty with the Catsups. (Who vanished without a trace for over a hundred years. A handful of them resurfaced in 1990 with a proposal to build a casino on “tribal land,” which they had determined to be a few blocks of Broadway between Morrison and Salmon in downtown Portland. A decision is still pending.)

Colonel Heinz Mustard resigned his commission shortly after returning from the northwest and set himself up in business, producing and bottling the new version of red mash. But he didn’t like the name. So, after trying out at least 56 possible names, he finally settled on … salsa! Informed that Mexico had already trademarked that term, he quickly changed the name to his 57th choice: ketchup. (Hell, he was German. Couldn’t spell worth a damn in English.)

And then …

Well, I was going to add a few more risible details and somehow end up with the punchline “Mustard’s Last Stand.” But you all saw that coming a mile away, didn’t you? I’ll leave the completion of this little fable as an exercise for the student.

(There really is a wild root called the wapato growing on Sauvie Island, and the Indians of the area really did gather it and eat it, though probably not with red mash. All the rest of the story should be taken with a grain of salt. Possibly an entire sprinkle of salt, and pepper, and maybe a slice of Bermuda onion.)

April 15, 2000

Sauvie Island, OR