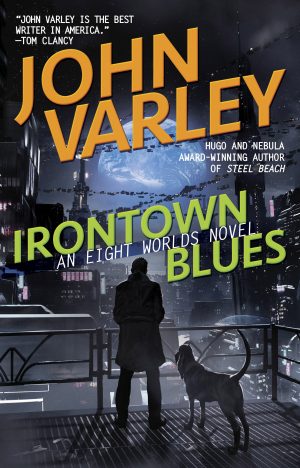

Irontown Blues – Excerpt

The dame blew into my office like a warm breeze off the Pacific. In other circumstances I’d have loved to invite her to do the jitterbug all night long at the Santa Monica Pier to the swinging clarinet of Artie Shaw and the Gramercy Five.

Too bad about the para-leprosy.

She was dressed in retro noir fashion. Her face was a vague outline behind a heavy veil hanging from a hat that had what looked like a peacock on it. Not just the feathers, the whole peacock. Her blouse had frills at the throat, and her jacket had enough shoulder padding that she could have balanced two martini glasses on them. Her shoes had blocky, four-inch heels and open toes, exposing two nails painted carmine. I was willing to bet that her stockings had seams down the back.

Not that I was in any position to scoff at her. She might actually have dressed to fit the setting. My own office could have been transported complete from another era by a time machine.

A rack for hats and coats stood in one corner, with an assortment of hats in various shades of gray. A trench coat hung from one of the hooks. Next to it was a tall metal file cabinet. A ceiling fan above us stirred the air in a desultory fashion. The view out the window was of a pawnshop’s neon sign, flashing red and green. In a moment of nostalgic overkill one day I had a paper wall calendar made, and I hung it on the wall. The page showing said April, 1939, the month Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep was published. The artwork above was an illustration of what was known as a pinup girl, dressed in a skimpy bathing suit. Well, skimpy for 1939, anyway.

Most of my office was as phony as the calendar.

The filing cabinet was empty.

The view from the window was a screen animation.

The bloodhound sleeping in the corner was real.

There was no way to tell that we were in a building in a man-made canyon in Luna and that the date was centuries after 1939.

I noticed her gloves. They were gray leather, but there was something wrong with the ends of the fingers. Everything else seemed just the right amount in just the right places.

“Come on in,” I said, standing and gesturing to the comfortable oxblood-leather chair in front of my desk. She hesitated a moment longer, then closed the door and walked to the client chair.

“Can I get you a drink? Coffee? Bourbon?”

“No thank you.” She turned slightly and gestured to the door. “Am I speaking with Mr. Sherlock or Mr. Bach?”

Printed in gold letters on the pebbled glass in the upper half of the door behind her—backward from here—were the words

Sherlock & Bach

Discreet Private Investigations

“I’m Chris Bach,” I said. “Sherlock is my associate, but I only bring him in on certain cases.” In the corner behind her, Sherlock lifted his head from the rug and regarded me dubiously, which is the only way he ever regards anyone. He sniffed the air once, didn’t seem entirely happy with that, and tried it again. Then he got to his feet, eighty pounds of sad-eyed bloodhound, slouched over to where she sat, and sniffed at her glove.

I was surprised. Sherlock is one of the laziest dogs in Luna and likes to affect a smelled-it-all attitude. A scent that would get him up off his precious rug and across the room for a better sniff must be something very interesting indeed.

The girl was startled to see his huge nose almost touching her left glove, started to jerk it away, then decided against it. Sherlock snuffled up and down the hand, then turned to me and made what I had always interpreted as his version of a shrug. Then he ambled back to his corner and circled around a few times. He lowered his massive head and returned to the serious business of the afternoon nap.

“Now, what can I do for you, Ms. . . .”

“Smith,” she said. “Mary Smith.”

We professional private detectives train ourselves to keep a poker face.

“I’d like you to find someone for me,” she went on. Ninety percent of potential clients want me to follow someone around. Finding someone is usually more interesting.

“What’s the party’s name?”

“I don’t know.”

Not necessarily a problem.

“Male or female?”

“The last time I saw him, he was male. But he changes a lot.”

A problem Philip Marlowe never had to face. But then I’ve got resources Phil never had. It evens out.

“Why don’t you just start from the beginning?”

“I think I’d better start from the end,” she said. She took a deep breath and carefully pulled off one of her kid gloves. It was as if she was so delicate she was afraid not all the fingers would stay in place.

It turned out to be literally true; the ends of all her fingers were missing.

At the last joint on three of them, and the second joint on the ring finger, was what looked like pink scar tissue. The thumb was intact, but the nail was thickened and twisted, and a painful bluish color. The rest of the hand was covered with an angry red rash.

She let me look at it for a moment, then slipped her glove back on.

“I assume you’ve heard of lepers?” she said.

“Heard of them, of course. I’ve even seen one or two.”

It’s not as if people throw stones and shout “unclean!” as they apparently did in ancient times, back on Old Earth, but lepers are not really welcome in the mainstream of society these days.

Extreme body modifications have been around for a long time, from pierced cheeks to split penises, and that was back in the days when you couldn’t unsplit one. These days you can keep a human head alive with no body at all, or elect to have your arms and legs removed for a few weeks, then put back on later. Or not, if that’s your twist. It’s all socially acceptable. Ain’t modern medicine wonderful?

Altering your appearance with engineered diseases has gone through several fashion stages. One decade it’s very in to sport a suppurating case of psoriasis or tertiary “syphilis,” then all of a sudden no one wants to see your faux warts and rashes. Lately it’s all pretty out. You had to go to some pretty weird dives to see disease heads.

“I have never seen one. It’s not my scene at all. But one night I was out enjoying myself . . . enjoying myself rather too much, I guess. I’d had too much to drink. I met a man who seemed nice enough. We talked. One thing led to another, and we ended up in one of the private rooms at the back of the club.”

“Which club was this?” I asked, getting out my notebook and pen.

“The Passing Glance,” she said. “Level Fifty-six, at the corner of King and Main.”

“I know the place.”

“I went there when some friends suggested I’d like the floor show. Not an avant-garde sort of place at all. In fact, definitely retro.” The lady had been slumming, thirty levels from her natural habitat.

“In retrospect, I remember a blister at one corner of his mouth. I discounted it. You know how some people will indulge in a ‘beauty mark’ here and there.

“The next morning I found my hands were all scaly. Mr. Bach, I’m convinced that he meant to infect me.” Up to then her voice had been calm and even. Now there was some heat in it. “That he got a kick out of it. They call it ‘exporting.’ The idea is to spread your pet disease to as many straight people as possible.”

I thought that I had heard it all, but I admit that was a new one on me. New, and highly illegal. If you are into genetically engineered diseases, they must be killed diseases. Noncommunicable. Like old-fashioned vaccines, before humanity really had a good handle on genetics.

I could tell I was going to be looking for a real sicko.

She made a deliberate effort to calm down.

“I think I’d like that bourbon now, if you don’t mind,” she said.

I got the office bottle from a drawer in my desk. It says Jack Daniel’s on the label, but of course it had never been within a quarter million miles of Kentucky. I once had a sip of the real thing, over two hundred years old and costing more than a year’s salary from my old job as a bobby, and was disappointed to find that this ersatz stuff tasted just as good. You would think there would be something special about one of the last bottles of booze remaining from Old Earth.

I got two tumblers that looked pretty clean from the drawer. I poured two generous slugs. When the neck of the bottle touched the rim of the first glass, Sherlock’s head came up and he huffed once to show his contempt, then got up. He ambled over to the door and stepped on his touchplate, which opened it for him. He hurried through. Alcohol is not one of Sherlock’s favorite scents.

Also, I sometimes drink a bit too much. It’s a sad thing when your dog disapproves of you.

“That’s quite a . . .”

“Large dog?”

“He’s beautiful.”

That was never a word I would have applied to Sherlock, but I warmed to her a little for the first time. She was clearly a dog person.

She reached for the glass with both hands, carefully positioned it in the left one, and raised the veil slightly with the right. I caught a glimpse of ravaged features. I had no desire to see any more.

“What’s his name?”

“Watson,” I lied. “He’s a pedigreed bloodhound. His nose is very sensitive, and he doesn’t like alcohol.” I’ve always wondered how bad the smell of Jack could be to an animal that thought sniffing another dog’s rectum was the height of pleasure.

“That would sort of spoil his fun, wouldn’t it? Warning me?”

We were back to the leper. I was far from convinced it had all happened the way she said.

“What do you plan to do to him once I’ve found him? If you intend to cause him physical harm, I can’t help you.”

“I’m going to take him to court. But I haven’t finished. Giving me this stuff was bad enough, but normally I’d just chalk it up to experience. I should have been more careful, I’m not denying that. So when I started breaking out, I just went to the medico and told him to cure it.

“But he couldn’t cure it.”

Her story, apparently, was that it could not be cured. Which I had a great deal of trouble believing. But for a bad moment there I felt a little thrill of atavistic fear, fear of something no one has worried about much for many generations: What if she gives it to me?

At some point in human history between the discovery of fire and the invention of ice cream—humanity’s greatest moment, so far—being eaten by animals stopped being an everyday thing to worry about. It could still happen on Old Earth so long as wild animals remained, but most days you could go about your business—say, in the middle of Manhattan Island—without taking any particular precautions about it.

After the Earth was taken away from humanity by the Invaders, your chances of being preyed upon grew pretty slim since all the feral lions and tigers and bears remained on Old Earth.

It was much later that we were able to stop worrying about disease. It had been several hundred years since anyone got sick from anything other than a self-inflicted condition, i.e., drinking yourself shit-faced and waking up the next day feeling like death. And a damn good thing, too. It would be hard to imagine a better environment for germ-caused disease than the close quarters typical of a Lunar city.

The idea that there might be something incurable out there, something that made your face look like a cross between a beet and a potato, was not a tempting thought.

“So you’re telling me this stuff is incurable?”

“Well, no.” She suddenly seemed to realize what I was thinking, and held out a hand, palm up. “Oh, no, believe me, if I were still contagious, I’d never have come here. I wouldn’t dream of inflicting this on anyone else.”

I motioned for her to go on.

“It’s just that the medico couldn’t cure it. He referred me to a gentech lab. They treated me like a fascinating new animal they had discovered. They couldn’t cure this thing in one simple step, apparently. Something about its becoming bound up in my genes. They had to make their own custom nanobots to attack it, and they did it in stages. They say I should be back to normal in another week.”

I knew her story was not all true, and so what? Clients lie. Every private detective learns that. It’s just something you have to work around.

So I opened a desk drawer and got out a standard contract and a pen. She held the pen awkwardly, obviously not having handled one since school, where they still require a minimum of handwriting skills. One day they’ll drop the requirement, and we’ll finally have achieved that long-predicted goal: the paperless, fully computerized society. And I’ll be in big trouble.

When she handed it back, I glanced at the information, written in careful block letters. Under profession she had written artist. I trust I didn’t betray any reaction. Half the nonemployed drones in New Dresden were “artists.” What they produced, God alone only knew.

I quoted her my standard rate, a point at which about half my prospective clients hit the road without hiring me. For some reason, many of them expect this sort of work to be cheap. Miss Smith didn’t complain. Usually, clients want to thumb payment to me, and they look surprised with I tell them I prefer cash. She had money at hand, in the form of a roll in her purse. She counted out my retainer and laid it on the desk.

“I’ll itemize expenses, which you also pay for. If I have to go to Mars or beyond, I’ll check with you first.”

She nodded. I escorted her to the door and watched her striding down the hallway toward the elevator. So did Sherlock, and after a cautious sniff of the air, he lumbered back into the office before I shut it. He resumed his customary position on the shaggy rug in the corner, first circling it a few times to get his bearings, then plopping down and giving a sigh.